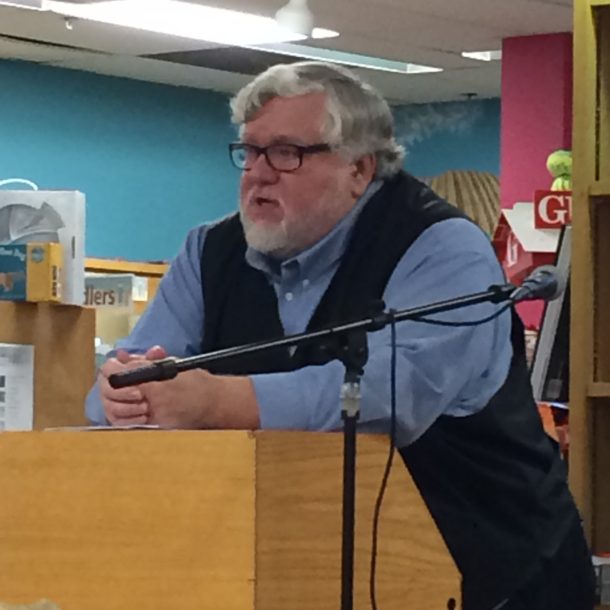

Episode 009 - The Craft and Business of Short Fiction with Tony Conaway

April 10, 2017

|

Tony Conaway has been a published writer since 1990. He has written dozens of nonfiction articles for venues as varied as airline in-flight magazines, business publications, men’s magazines, and medical publications. These days, he is concentrating on his fiction writing. At present, he has had over thirty short stories published, some of which have been collected in seven anthologies.

|

His fiction spans a wide variety of genres, including serious fiction, science fiction, mystery and noir, historical fiction, and humor. His odder writing gigs include writing someone else’s memoir, a script for a planetarium show, and co-writing jokes performed by Jay Leno on “The Tonight Show.”

|

Matty Dalrymple: Hello and welcome to Episode 9 of the Indy Author Podcast. Today, my guest is Tony Conaway. Tony has been a published writer since 1990. He’s written dozens of nonfiction articles for venues as varied as airline in-flight magazines, business publications, men’s magazines, and medical publications. These days, he’s concentrating on his fiction writing. At present, he’s had over 30 short stories published, some of which have been collected in seven anthologies. His fiction spans a wide variety of genres, including serious fiction, science fiction, mystery and war, historical fiction, and humor. His odder gigs include writing someone else’s memoir, a script for a planetarium show, and co-writing jokes performed by Jay Leno on The Tonight Show. Today, we’re going to talk about the craft and business of short story writing. Welcome, Tony.

Tony Conaway: Thank you, Matty. A pleasure to be here.

Matty: I want to start out with the writing of short stories and start talking about how the sensibility for short story writing might be different than longer fiction. My father, who my publishing company has named after—his pen name was William Kingsfield—had a lot of success with short stories in the 50s. He got some stories published in Colliers and Cosmopolitan. Once he started having that success, he thought, “Oh, now I’m going to try a novel,” and I think he just had the short story sensibility more than he had the novel sensibility because it never really happened for him, in the novel writing area the way it did for him in the short story writing area. Do you think it’s really two different approaches or two different sensibilities to write those different kinds of fiction?

Tony: Certainly there are different characteristics to writers who succeeded at novels and writers who succeed at short stories, although, there are writers who do succeed in both. The ability to sustain the effort to finish a novel—you’ve written two or three novels now, you know that it can easily take a year to do an entire novel. Even if you’re working on it full-time, which a few of us had the leisure to do.

Short story is something that can be knocked out very quickly, especially if you’re doing flash fiction. I finished a short story in three hours this past week. It was about 1250 words, which was about right. I can write 500 words an hour so that last part was 250 words but I had to do a little bit of research for it.

Matty: When you write that kind of story, is there an editing process that goes along with it or is your approach more that, when you finish the three hours, you finish the story?

Tony: Oh, if only that were true. No, the editing goes on forever. One of my problems in the past has been when is it finally done because you look at it and you start second guessing yourself and make changes so the editing process continues indefinitely. As you change things, I know, at least speaking for myself, that I’m more likely to have made an error or a typo because I’ve changed things.

I sent that short story off to a critique session from the Brandywine Valley Writers Group, of which we’re both members. After sending it, I noticed that some of the last changes I had made resulted in typos. There’s one sentence that was originally had a singular subject, I had put in compound subjects and that was plural and I didn’t change the verb tense. That sort of thing is very easy to do with your editing.

Matty: Do you have beta readers or friendly readers who look through your work before you send it out?

Tony: By and large, that’s what my critique groups are for. If, for whatever reason, I have to get something out more quickly than waiting for the next critique group, there are a few people that I can go to and just say, “I need to get this in the mail by Thursday. Would you mind reading it and letting me know what you think.” But for the most part, I have one trusted critique group that meets twice a month and there are other critique groups that occur on an irregular basis so I’m pretty well covered in that regard.

It would be rare for me to have no critique group for a month. That almost never happens the way things have been arranged. It took many years to get into that situation. I remember when I was a member of the first group I joined, the Brandywine Valley Writers Group, for the first few years, I was trying to get into a critique group. They had one critique group that met separately from the main group and they kept falling apart and rescheduling their events and so on and it never happened through them.

Matty: Did you have a hand in forming the groups that you’re a member of now or did you come upon them in some other way?

Tony: I did eventually become president of the Brandywine Valley Writers Group so I may have facilitated that. But most of the critique groups came through two other groups that I was in, the Main Line Writers Group, of which I’m vice president, and the Wilmington Writers Group, in which I more or less have the same status. There was another critique group that I found online down in Delaware. I should mention that we both live in Pennsylvania but not far from the Delaware border. That group lasted about two or three years and was not all that useful to me because most of the people in the group were not published authors and they didn’t feel the urgency to become published authors. They all wanted it. I felt they didn’t want it badly enough. They weren’t sending things out. They weren’t finishing stories and so on, so you do have to have the right people in the critique group.

Matty: I know that this is a little bit off the topic of the short stories but one of the challenges I’ve seen with critique groups is that if you have a group of six people, you’re likely to get six opinions on what you’ve written. I decided to go the “just one editor” route so I was at least getting it all through one set of eyes. Do you ever find that to be a challenge of juggling all the input you’re getting from the different members?

Tony: I do like to have several eyes looking at my work because it often takes that to find all the typos and all the punctuation errors and so on, that inevitably seem to creep into a manuscript. Other than that, I don’t have a lot of problem discounting a member. I know their opinions going to be bad, unless they come up with a typo that I want to fix, the odds are I’m not going to pay any attention to them. We had a young guy who was wont to say, “I hate your character so much, I wish a giant meteor would come down and crush him.”

Matty: [Laughs] Wow!

Tony: Yeah. He didn’t hold back and I just thought, “Yeah, that’s him. Just move on.” You know the people who are good writers, listen to them. I can say one thing that I would like to mention. I would like to be in a critique group that’s composed of writers who are more accomplished than I am and that’s something I haven’t found perhaps because I’m older, perhaps because I’m been writing for so many years, I tend to be the most accomplished person, the one who’s been published the most and so on, in most of my critique groups.

Matty: That’s okay to fill that role occasionally but you don’t want to be filling that role all the time because you’re losing a lot of the benefit you want to be getting out of that group. Your comment about the guy and the meteor makes me think that there’s a whole podcast episode on having a thick skin.

Tony: Yes.

Matty: When you’re doing the editing of a story, are you more likely, not from a proofreading point of view but from a content point of view, to be going back and removing material you’ve put in a first draft or adding more material to a first draft?

Tony: It depends in part upon the genre and I do write in many different genres. Especially, when it is a mystery, especially, when it is science fiction, I feel that there has to be an internal logic. When I go back, what tends to happen is I say, “Gee, this could have happened another way. This part wasn’t explained that well.”

I’m apt to add another few sentences to explain a plot point or solve an issue where a reader might say, “Well what if it happened this way?” On the other hand if I’m writing literary fiction, I think I’m more apt to cut something out. If I’m writing humor, it’s just, is it funny.

Matty: I would think that with humor, usually shorter would be better. Is that true?

Tony: Generally, yes. But I think it’s more of the positioning of the humor. You almost always want the punch line or the word that gets the laugh to be at the end and sometimes it’s difficult to arrange your sentences so that they come out that way.

Matty: I was talking with Jim Breslin at an earlier episode. We were talking about storytelling and his involvement with the Story Slam and how he carried forward the things that he had learned from his Story Slam experiences into his own writing. One of the things he was talking about was flash fiction and how you really have to make every word count and in that scenario, you sort of refine, refine, refine down to as concise a presentation as you can.

I think that, probably one of the differences I would expect between people who are better at short stories and people who are better at novels is that when I’m writing, I always think of other things that I would enjoy putting in to set the scene or create the mood or describe the environment. You were nice enough to read a short story I had done for my Ann Kinnear readers. I had written an Ann Kinnear short story to hopefully tide my Ann Kinnear followers over until the next Ann Kinnear novel is ready.

But my tendency was always to, “Oh, it’s going to be really interesting if I can add this little description of the scene or add this little blurb about what somebody is doing.” I think that that would be maybe one of those things that distinguishes someone whose heart is really in novels or heart is really in short stories.

Tony: Yes, indeed.

Matty: We’ve talked a little bit about the process of writing a story and I want to also talk about the mechanics of getting short fiction works published. Can you talk a little bit about what outlets you use, what advice you would have to people who maybe have a short story now they’re looking for somewhere to get it out into the world?

Tony: Well, it’s certainly changed quite a bit since I started writing in 1990. Back then, my goal every week was to send out queries because these were all done by snail mail, send out queries or the entire story depending upon what the source wanted or the venue wanted and I want to send out eight a week. Knowing that within a month, because it took at least that long, I had a good chance of getting some response every day of the week, getting seven responses in a week.

There will always be one that just disappeared and never got a response. Nowadays, thankfully, we do it all by email, there are very, very few places that require written copies and it’s a lot easier as well as cheaper to send things out. I use a source called Duotrope. They do charge to use Duotrope, it’s only $50 a year, though. Duotrope not only has the information and the links to the websites of many, many venues, it also has some additional features that I find very useful, including a way to keep track of what’s been sent out, how long it typically takes to get a response from, and what the final result was. It will even try to catch you if you make a mistake if a publication lists itself as not accepting simultaneous submissions, as you input the information into the Duotrope submissions guide, it indicates you’ve sent it out to more than one place and one of them does not want people to send out simultaneous submissions. It will say, one of the places you sent to already doesn’t want you to send it out anyplace else.

Matty: How long does it normally take for a place that you send it to, to respond so that if they haven’t accepted it, you can then move on to other platforms?

Tony: It varies considerably. If your goal is to write for literary magazines, many of them are associated with colleges, it’s going to take a lot longer if you send it out in the summer time because the slush pile, even though there’s no longer an actual pile since it’s done virtually over the internet, the first readers of almost all of the submissions will be college students so when they’re away for the summer, they’re just going to sit there.

Other than that, there are a few venues that will get a response to you typically within one or two weeks. Most of them take on the order of two or even three months but there are places that take longer. One of the things that always surprised me is that there are two very similar mystery magazines. One is Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, the other is Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. They’re both published by the same publishing house. They look very, very similar but Ellery Queen gets things back to you fairly promptly. Alfred Hitchcock, which has a different editorial staff, takes forever. It can take a year to get a response, and both of these places want exclusivity in the submissions so I’ve never seen anything to Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine because I don’t want to wait a year just for them to reject something.

Matty: Does Duotrope or some other platform give you any advice about what is going to make a short story more appealing to a certain periodical, for example?

Tony: The way Duotrope does it is that they like to interview the editors of the publication and they’ll ask them questions which would help. But generally for that information, you need to go to the website and there will always be submissions guidelines and the editor should tell you exactly what they’re looking for.

It’s not uncommon for a magazine that publishes supernatural things to say, “We are sick of vampire stories, so we don’t want any. Or if you do a vampire story, it better be the best damn vampire story that has ever been written.”

Matty: When you’re writing stories, have you ever identified a magazine that you want to get published in and you’re writing a story for the magazine? Or do you always write the story, then you go looking for the platform for it?

Tony: Most of the time, I’m inspired in some way and I write a story and then I go looking for it. However, another thing that Duotrope does for your $50 a year is every Tuesday morning, they will send you an updated list of places that are looking for stories. It could be anthologies, it could be magazines, it could be websites. It also breaks them down into places that will pay for your work, places that don’t pay, and they add other things like places that we believe are now defunct. It even gives a deadline saying, “This anthology needs stories by the end of this month to be considered.”

Sometimes, every once in a while, I have written a story specifically for an anthology that wants something. Rarely have I found that story gets accepted. Someone wanted a gay, humorous zombie story and the character had to be gay. I knocked the thing off. I thought it was okay, not necessarily my best work. They didn’t accept it. Afterwards, I was stuck with this thing, as nobody’s going to want this weird story. Generally, I think it is better just do your best work and then try to find. The exception would be if an editor asks me specifically, “I need a story of this sort,” and then I’d be happy to provide one for them.

Matty: How do editors know about that? Is it that from your experience in networking or is there also a market for matching up the editors with writers in that way?

Tony: That is primarily a networking thing. There is, at least in the professional area of publication, a lot of moving about: you edit this place, then if that folds, you go to another job, and so on. What you hope for is that editor knows that you’re reliable and no matter where they go, they’ll call upon you for a story.

I’ve written eleven business books that I collaborated on, and book #1, book #3 and book #4 were all written for the same acquisitions editor, but at three different publication houses as he kept moving around. He was a rather gruff guy. He could be difficult to deal with, so it didn’t surprise me he got let go by a number of firms. But he always asked us to produce a story, once we got connected with them first time, and he was very happy with first book. It’s good to get on the good side of an editor. That seems to be easier to do in book publishing and nonfiction than in fiction. In fiction, there seems to be even more moving about, perhaps because there’s less money in fiction than in nonfiction.

Matty: Do you feel like the short story market is trending up or down or staying steady in the time that you’ve been involved in it?

Tony: With a few exceptions, I think it’s pretty much the same. I think more people are finding that it is not all that difficult nowadays to publish an anthology. Print on demand makes books relatively easy to do, and programs that do formatting for you since the formatting is critical. People could put together an anthology who would not consider doing that before.

As for magazines, there is so little money in magazines nowadays. I don’t see a lot of expansion. Something new may crop up and two other things may have folded. There are websites that come up all the time, very few of which pay any money. That area maybe increasing as well.

Matty: You’ve mentioned anthologies a couple times. Can you describe the mechanics behind the creation of an anthology?

Tony: Well, I’ve never done it myself, by myself. I’ve been involved in the publication of one anthology. We’re currently working on another through the Main Line Writers Group. The first time we did it, we were fortunate enough to have someone who would create spreadsheets and schedules to do the whole thing. It very much helps to have someone who’s anal-retentive on your team and can keep you on point and on schedule. That helped, although they’re still on the galleys. They were still a lot of errors, including ascribing one story to the wrong person, and a page of artwork that got dropped so the version that was finally printed had to have those corrected.

Matty: Were the people who were contributing an existing association of writers who got together and decided to do the anthology, or was there a driving force that was soliciting stories from people?

Tony: I would say more of a driving force. It was a decision by the current president of the Main Line Writers Group, Gary Zenker, that he wanted to do an anthology, so he told everyone what to expect. We went out for that one. We hired two editors. They called themselves the Gemini Group. They were the ones who decided which stories were good enough and ready to be published in that anthology. I submitted two stories, they rejected one, and some people who had had stories published elsewhere and submitted them, were also rejected. We didn’t always agree with their decisions but we decided, “Well, we’re paying for them to do this, we’re going to accept it this time around.”

One of the reasons we had them do it is no one in the group felt all that comfortable telling people, “No, your stories are not good enough for this.” This time around we decided, “You know, that cost us extra money, that took extra time, we’re just going to bite the bullet, and these are the editors, they are going to decide. You don’t like it, too bad. Go form your own group.”

Matty: They can be guests on the thick-skinned podcast episode when I get around to that. If you submit your story to a publication or an anthology, and they accept and publish it, what rights are you giving up? I’m asking this a little bit selfishly because I wrote the Ann Kinnear short story and at some point, I will have a collection of these and I’ll be able to put them together in a book. What rights might I be giving up if I were to get that story published in a periodical or some other outlet?

Tony: It varies depending upon what the periodical or anthology requests. I have an odd rejection letter—not really a rejection letter—that I got last week, but I should mention, I talked to other people who are so proud that they have one story being submitted somewhere, and my goal is to have 25 out every single month.

Matty: Twenty-five new stories you’ve written?

Tony: Not usually 25 new stories. I mentioned earlier, there are venues which will allow simultaneous submissions and those that won’t. If I send to a venue that does not allow simultaneous submissions, it has to be someplace I really want to get into, and they probably pay money. Some months I send out five stories to each of them to five different venues, but more likely there’s one or two venues I’ve sent to that don’t allow simultaneous submissions. Or it may be an anthology, and they have very specific needs like gay zombie stories.

The ultimate goal is at least 25 submissions. It may be for five stories, it may be for seven or eight stories. A few months ago, I made an effort to try to get stories that I’d already written republished, so I had about 10 stories out. I had over 30 submissions because a number of them were older stories I had published and there are fewer publications that will accept reprints.

Matty: And what about rights, if you want to use it in another way later on.

Tony: It will say specifically on the guidelines, or certainly should say, what rights they’re buying. The old thing that used to be done was “First North American Publishing Rights,” which meant they had the right to be the first people to publish it in North America. If you can get it published in Germany or England, go ahead, it’s got nothing to do with them.

Usually, they wanted the right to reprint it. Although, what you wanted ideally if they reprint it, say they do a ‘Best Of’ anthology, you want more money from them. Sometimes, they didn’t offer that. Usually, there was something else saying, we will receive exclusive rights to the story for a certain period of time. It may be six months, it may be longer.

I was mentioning earlier that I had received a letter about a story last week and this particular publication sent a rather odd letter saying they’d like me to resubmit it in April. Apparently, they don’t have a month-long memory. But they also want eighteen months exclusivity. I’m just not going to give them that. That’s too long. I will resubmit in April but I’ll say, “I’m sorry. Like this story? I’m going to republish it in my own—” not really anthology, a collection since they’ll all be my stories, “— and I’m not going to wait 18 months so you can have six months. Take it or leave it.” They’re only paying a penny a word and it’s about 800 words long so there’s not a lot of money at stake here.

Matty: So they wanted 18 months—not 18 months after they had published it; they just wanted to hold it for 18 months while they decided whether to publish it or not?

Tony: No, that was 18 months after publication, and it could be several months until it would get published.

Matty: Is there anything, when an author is working with a platform that might want to publish their work, that they should watch out for from either a legal or a creative point of view?

Tony: Well, since there isn’t that much money in writing short fiction, you generally don’t have the things you have to worry about when you’re writing novels or full-length nonfiction books. My first nonfiction book had something in the contract when it’s a much more extensive contract than you would usually get with short fiction, especially when you’re talking about one single story. The first one had a line about, “Can republish this in any form or venue, including those that have not yet been invented.”

Matty: That seems a little dicey.

Tony: Yes. We didn’t know that at the time, and because we’re talking about the early 1990s, CDROMs came out. I got in the mail a solicitation for a CDROM of my first book, which I had co-authored, from a totally different company. I was certainly surprised by it. We went back to the publisher and said, “What’s going on here?”, because they weren’t planning to give us any more money.

They said, “This clause in the contract allows us to do that.” It was underhanded in that they did it and didn’t bother to tell us, but it wasn’t illegal.

Fortunately, that publisher wanted another book from us so we held their feet to the fire the next time and said, “If you want to do it and you want another book, you’ve got to take this contract and delete that clause.” From now on, that’s done. There are still difficulties with publishers. For example, one of the more successful business books that we’ve written has been republished in several countries and in several languages and we are, at the very least, supposed to get copies of it in those languages. We got the Korean version, we got the Japanese version, but there were several others that we never got. They just didn’t get around to it. I believe there’s a Vietnamese version, but that’s a pirated version.

The other day, as a gift for my former collaborator, I gave her a copy of the Russian edition, which I had to go on Amazon and buy and have sent from Russia. I had to pay for this thing in Euros which I should have gotten for free.

Matty: It’s still exciting to see your work in all those languages. That’s very exciting.

Tony: Yes, it is.

Matty: I appreciate you going over both the art and the business, sometimes the underhanded business, of short story writing. I think that’s going to be really helpful to people. Thank you, Tony.

Tony: My pleasure. Thank you, Matty.

Tony Conaway: Thank you, Matty. A pleasure to be here.

Matty: I want to start out with the writing of short stories and start talking about how the sensibility for short story writing might be different than longer fiction. My father, who my publishing company has named after—his pen name was William Kingsfield—had a lot of success with short stories in the 50s. He got some stories published in Colliers and Cosmopolitan. Once he started having that success, he thought, “Oh, now I’m going to try a novel,” and I think he just had the short story sensibility more than he had the novel sensibility because it never really happened for him, in the novel writing area the way it did for him in the short story writing area. Do you think it’s really two different approaches or two different sensibilities to write those different kinds of fiction?

Tony: Certainly there are different characteristics to writers who succeeded at novels and writers who succeed at short stories, although, there are writers who do succeed in both. The ability to sustain the effort to finish a novel—you’ve written two or three novels now, you know that it can easily take a year to do an entire novel. Even if you’re working on it full-time, which a few of us had the leisure to do.

Short story is something that can be knocked out very quickly, especially if you’re doing flash fiction. I finished a short story in three hours this past week. It was about 1250 words, which was about right. I can write 500 words an hour so that last part was 250 words but I had to do a little bit of research for it.

Matty: When you write that kind of story, is there an editing process that goes along with it or is your approach more that, when you finish the three hours, you finish the story?

Tony: Oh, if only that were true. No, the editing goes on forever. One of my problems in the past has been when is it finally done because you look at it and you start second guessing yourself and make changes so the editing process continues indefinitely. As you change things, I know, at least speaking for myself, that I’m more likely to have made an error or a typo because I’ve changed things.

I sent that short story off to a critique session from the Brandywine Valley Writers Group, of which we’re both members. After sending it, I noticed that some of the last changes I had made resulted in typos. There’s one sentence that was originally had a singular subject, I had put in compound subjects and that was plural and I didn’t change the verb tense. That sort of thing is very easy to do with your editing.

Matty: Do you have beta readers or friendly readers who look through your work before you send it out?

Tony: By and large, that’s what my critique groups are for. If, for whatever reason, I have to get something out more quickly than waiting for the next critique group, there are a few people that I can go to and just say, “I need to get this in the mail by Thursday. Would you mind reading it and letting me know what you think.” But for the most part, I have one trusted critique group that meets twice a month and there are other critique groups that occur on an irregular basis so I’m pretty well covered in that regard.

It would be rare for me to have no critique group for a month. That almost never happens the way things have been arranged. It took many years to get into that situation. I remember when I was a member of the first group I joined, the Brandywine Valley Writers Group, for the first few years, I was trying to get into a critique group. They had one critique group that met separately from the main group and they kept falling apart and rescheduling their events and so on and it never happened through them.

Matty: Did you have a hand in forming the groups that you’re a member of now or did you come upon them in some other way?

Tony: I did eventually become president of the Brandywine Valley Writers Group so I may have facilitated that. But most of the critique groups came through two other groups that I was in, the Main Line Writers Group, of which I’m vice president, and the Wilmington Writers Group, in which I more or less have the same status. There was another critique group that I found online down in Delaware. I should mention that we both live in Pennsylvania but not far from the Delaware border. That group lasted about two or three years and was not all that useful to me because most of the people in the group were not published authors and they didn’t feel the urgency to become published authors. They all wanted it. I felt they didn’t want it badly enough. They weren’t sending things out. They weren’t finishing stories and so on, so you do have to have the right people in the critique group.

Matty: I know that this is a little bit off the topic of the short stories but one of the challenges I’ve seen with critique groups is that if you have a group of six people, you’re likely to get six opinions on what you’ve written. I decided to go the “just one editor” route so I was at least getting it all through one set of eyes. Do you ever find that to be a challenge of juggling all the input you’re getting from the different members?

Tony: I do like to have several eyes looking at my work because it often takes that to find all the typos and all the punctuation errors and so on, that inevitably seem to creep into a manuscript. Other than that, I don’t have a lot of problem discounting a member. I know their opinions going to be bad, unless they come up with a typo that I want to fix, the odds are I’m not going to pay any attention to them. We had a young guy who was wont to say, “I hate your character so much, I wish a giant meteor would come down and crush him.”

Matty: [Laughs] Wow!

Tony: Yeah. He didn’t hold back and I just thought, “Yeah, that’s him. Just move on.” You know the people who are good writers, listen to them. I can say one thing that I would like to mention. I would like to be in a critique group that’s composed of writers who are more accomplished than I am and that’s something I haven’t found perhaps because I’m older, perhaps because I’m been writing for so many years, I tend to be the most accomplished person, the one who’s been published the most and so on, in most of my critique groups.

Matty: That’s okay to fill that role occasionally but you don’t want to be filling that role all the time because you’re losing a lot of the benefit you want to be getting out of that group. Your comment about the guy and the meteor makes me think that there’s a whole podcast episode on having a thick skin.

Tony: Yes.

Matty: When you’re doing the editing of a story, are you more likely, not from a proofreading point of view but from a content point of view, to be going back and removing material you’ve put in a first draft or adding more material to a first draft?

Tony: It depends in part upon the genre and I do write in many different genres. Especially, when it is a mystery, especially, when it is science fiction, I feel that there has to be an internal logic. When I go back, what tends to happen is I say, “Gee, this could have happened another way. This part wasn’t explained that well.”

I’m apt to add another few sentences to explain a plot point or solve an issue where a reader might say, “Well what if it happened this way?” On the other hand if I’m writing literary fiction, I think I’m more apt to cut something out. If I’m writing humor, it’s just, is it funny.

Matty: I would think that with humor, usually shorter would be better. Is that true?

Tony: Generally, yes. But I think it’s more of the positioning of the humor. You almost always want the punch line or the word that gets the laugh to be at the end and sometimes it’s difficult to arrange your sentences so that they come out that way.

Matty: I was talking with Jim Breslin at an earlier episode. We were talking about storytelling and his involvement with the Story Slam and how he carried forward the things that he had learned from his Story Slam experiences into his own writing. One of the things he was talking about was flash fiction and how you really have to make every word count and in that scenario, you sort of refine, refine, refine down to as concise a presentation as you can.

I think that, probably one of the differences I would expect between people who are better at short stories and people who are better at novels is that when I’m writing, I always think of other things that I would enjoy putting in to set the scene or create the mood or describe the environment. You were nice enough to read a short story I had done for my Ann Kinnear readers. I had written an Ann Kinnear short story to hopefully tide my Ann Kinnear followers over until the next Ann Kinnear novel is ready.

But my tendency was always to, “Oh, it’s going to be really interesting if I can add this little description of the scene or add this little blurb about what somebody is doing.” I think that that would be maybe one of those things that distinguishes someone whose heart is really in novels or heart is really in short stories.

Tony: Yes, indeed.

Matty: We’ve talked a little bit about the process of writing a story and I want to also talk about the mechanics of getting short fiction works published. Can you talk a little bit about what outlets you use, what advice you would have to people who maybe have a short story now they’re looking for somewhere to get it out into the world?

Tony: Well, it’s certainly changed quite a bit since I started writing in 1990. Back then, my goal every week was to send out queries because these were all done by snail mail, send out queries or the entire story depending upon what the source wanted or the venue wanted and I want to send out eight a week. Knowing that within a month, because it took at least that long, I had a good chance of getting some response every day of the week, getting seven responses in a week.

There will always be one that just disappeared and never got a response. Nowadays, thankfully, we do it all by email, there are very, very few places that require written copies and it’s a lot easier as well as cheaper to send things out. I use a source called Duotrope. They do charge to use Duotrope, it’s only $50 a year, though. Duotrope not only has the information and the links to the websites of many, many venues, it also has some additional features that I find very useful, including a way to keep track of what’s been sent out, how long it typically takes to get a response from, and what the final result was. It will even try to catch you if you make a mistake if a publication lists itself as not accepting simultaneous submissions, as you input the information into the Duotrope submissions guide, it indicates you’ve sent it out to more than one place and one of them does not want people to send out simultaneous submissions. It will say, one of the places you sent to already doesn’t want you to send it out anyplace else.

Matty: How long does it normally take for a place that you send it to, to respond so that if they haven’t accepted it, you can then move on to other platforms?

Tony: It varies considerably. If your goal is to write for literary magazines, many of them are associated with colleges, it’s going to take a lot longer if you send it out in the summer time because the slush pile, even though there’s no longer an actual pile since it’s done virtually over the internet, the first readers of almost all of the submissions will be college students so when they’re away for the summer, they’re just going to sit there.

Other than that, there are a few venues that will get a response to you typically within one or two weeks. Most of them take on the order of two or even three months but there are places that take longer. One of the things that always surprised me is that there are two very similar mystery magazines. One is Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, the other is Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. They’re both published by the same publishing house. They look very, very similar but Ellery Queen gets things back to you fairly promptly. Alfred Hitchcock, which has a different editorial staff, takes forever. It can take a year to get a response, and both of these places want exclusivity in the submissions so I’ve never seen anything to Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine because I don’t want to wait a year just for them to reject something.

Matty: Does Duotrope or some other platform give you any advice about what is going to make a short story more appealing to a certain periodical, for example?

Tony: The way Duotrope does it is that they like to interview the editors of the publication and they’ll ask them questions which would help. But generally for that information, you need to go to the website and there will always be submissions guidelines and the editor should tell you exactly what they’re looking for.

It’s not uncommon for a magazine that publishes supernatural things to say, “We are sick of vampire stories, so we don’t want any. Or if you do a vampire story, it better be the best damn vampire story that has ever been written.”

Matty: When you’re writing stories, have you ever identified a magazine that you want to get published in and you’re writing a story for the magazine? Or do you always write the story, then you go looking for the platform for it?

Tony: Most of the time, I’m inspired in some way and I write a story and then I go looking for it. However, another thing that Duotrope does for your $50 a year is every Tuesday morning, they will send you an updated list of places that are looking for stories. It could be anthologies, it could be magazines, it could be websites. It also breaks them down into places that will pay for your work, places that don’t pay, and they add other things like places that we believe are now defunct. It even gives a deadline saying, “This anthology needs stories by the end of this month to be considered.”

Sometimes, every once in a while, I have written a story specifically for an anthology that wants something. Rarely have I found that story gets accepted. Someone wanted a gay, humorous zombie story and the character had to be gay. I knocked the thing off. I thought it was okay, not necessarily my best work. They didn’t accept it. Afterwards, I was stuck with this thing, as nobody’s going to want this weird story. Generally, I think it is better just do your best work and then try to find. The exception would be if an editor asks me specifically, “I need a story of this sort,” and then I’d be happy to provide one for them.

Matty: How do editors know about that? Is it that from your experience in networking or is there also a market for matching up the editors with writers in that way?

Tony: That is primarily a networking thing. There is, at least in the professional area of publication, a lot of moving about: you edit this place, then if that folds, you go to another job, and so on. What you hope for is that editor knows that you’re reliable and no matter where they go, they’ll call upon you for a story.

I’ve written eleven business books that I collaborated on, and book #1, book #3 and book #4 were all written for the same acquisitions editor, but at three different publication houses as he kept moving around. He was a rather gruff guy. He could be difficult to deal with, so it didn’t surprise me he got let go by a number of firms. But he always asked us to produce a story, once we got connected with them first time, and he was very happy with first book. It’s good to get on the good side of an editor. That seems to be easier to do in book publishing and nonfiction than in fiction. In fiction, there seems to be even more moving about, perhaps because there’s less money in fiction than in nonfiction.

Matty: Do you feel like the short story market is trending up or down or staying steady in the time that you’ve been involved in it?

Tony: With a few exceptions, I think it’s pretty much the same. I think more people are finding that it is not all that difficult nowadays to publish an anthology. Print on demand makes books relatively easy to do, and programs that do formatting for you since the formatting is critical. People could put together an anthology who would not consider doing that before.

As for magazines, there is so little money in magazines nowadays. I don’t see a lot of expansion. Something new may crop up and two other things may have folded. There are websites that come up all the time, very few of which pay any money. That area maybe increasing as well.

Matty: You’ve mentioned anthologies a couple times. Can you describe the mechanics behind the creation of an anthology?

Tony: Well, I’ve never done it myself, by myself. I’ve been involved in the publication of one anthology. We’re currently working on another through the Main Line Writers Group. The first time we did it, we were fortunate enough to have someone who would create spreadsheets and schedules to do the whole thing. It very much helps to have someone who’s anal-retentive on your team and can keep you on point and on schedule. That helped, although they’re still on the galleys. They were still a lot of errors, including ascribing one story to the wrong person, and a page of artwork that got dropped so the version that was finally printed had to have those corrected.

Matty: Were the people who were contributing an existing association of writers who got together and decided to do the anthology, or was there a driving force that was soliciting stories from people?

Tony: I would say more of a driving force. It was a decision by the current president of the Main Line Writers Group, Gary Zenker, that he wanted to do an anthology, so he told everyone what to expect. We went out for that one. We hired two editors. They called themselves the Gemini Group. They were the ones who decided which stories were good enough and ready to be published in that anthology. I submitted two stories, they rejected one, and some people who had had stories published elsewhere and submitted them, were also rejected. We didn’t always agree with their decisions but we decided, “Well, we’re paying for them to do this, we’re going to accept it this time around.”

One of the reasons we had them do it is no one in the group felt all that comfortable telling people, “No, your stories are not good enough for this.” This time around we decided, “You know, that cost us extra money, that took extra time, we’re just going to bite the bullet, and these are the editors, they are going to decide. You don’t like it, too bad. Go form your own group.”

Matty: They can be guests on the thick-skinned podcast episode when I get around to that. If you submit your story to a publication or an anthology, and they accept and publish it, what rights are you giving up? I’m asking this a little bit selfishly because I wrote the Ann Kinnear short story and at some point, I will have a collection of these and I’ll be able to put them together in a book. What rights might I be giving up if I were to get that story published in a periodical or some other outlet?

Tony: It varies depending upon what the periodical or anthology requests. I have an odd rejection letter—not really a rejection letter—that I got last week, but I should mention, I talked to other people who are so proud that they have one story being submitted somewhere, and my goal is to have 25 out every single month.

Matty: Twenty-five new stories you’ve written?

Tony: Not usually 25 new stories. I mentioned earlier, there are venues which will allow simultaneous submissions and those that won’t. If I send to a venue that does not allow simultaneous submissions, it has to be someplace I really want to get into, and they probably pay money. Some months I send out five stories to each of them to five different venues, but more likely there’s one or two venues I’ve sent to that don’t allow simultaneous submissions. Or it may be an anthology, and they have very specific needs like gay zombie stories.

The ultimate goal is at least 25 submissions. It may be for five stories, it may be for seven or eight stories. A few months ago, I made an effort to try to get stories that I’d already written republished, so I had about 10 stories out. I had over 30 submissions because a number of them were older stories I had published and there are fewer publications that will accept reprints.

Matty: And what about rights, if you want to use it in another way later on.

Tony: It will say specifically on the guidelines, or certainly should say, what rights they’re buying. The old thing that used to be done was “First North American Publishing Rights,” which meant they had the right to be the first people to publish it in North America. If you can get it published in Germany or England, go ahead, it’s got nothing to do with them.

Usually, they wanted the right to reprint it. Although, what you wanted ideally if they reprint it, say they do a ‘Best Of’ anthology, you want more money from them. Sometimes, they didn’t offer that. Usually, there was something else saying, we will receive exclusive rights to the story for a certain period of time. It may be six months, it may be longer.

I was mentioning earlier that I had received a letter about a story last week and this particular publication sent a rather odd letter saying they’d like me to resubmit it in April. Apparently, they don’t have a month-long memory. But they also want eighteen months exclusivity. I’m just not going to give them that. That’s too long. I will resubmit in April but I’ll say, “I’m sorry. Like this story? I’m going to republish it in my own—” not really anthology, a collection since they’ll all be my stories, “— and I’m not going to wait 18 months so you can have six months. Take it or leave it.” They’re only paying a penny a word and it’s about 800 words long so there’s not a lot of money at stake here.

Matty: So they wanted 18 months—not 18 months after they had published it; they just wanted to hold it for 18 months while they decided whether to publish it or not?

Tony: No, that was 18 months after publication, and it could be several months until it would get published.

Matty: Is there anything, when an author is working with a platform that might want to publish their work, that they should watch out for from either a legal or a creative point of view?

Tony: Well, since there isn’t that much money in writing short fiction, you generally don’t have the things you have to worry about when you’re writing novels or full-length nonfiction books. My first nonfiction book had something in the contract when it’s a much more extensive contract than you would usually get with short fiction, especially when you’re talking about one single story. The first one had a line about, “Can republish this in any form or venue, including those that have not yet been invented.”

Matty: That seems a little dicey.

Tony: Yes. We didn’t know that at the time, and because we’re talking about the early 1990s, CDROMs came out. I got in the mail a solicitation for a CDROM of my first book, which I had co-authored, from a totally different company. I was certainly surprised by it. We went back to the publisher and said, “What’s going on here?”, because they weren’t planning to give us any more money.

They said, “This clause in the contract allows us to do that.” It was underhanded in that they did it and didn’t bother to tell us, but it wasn’t illegal.

Fortunately, that publisher wanted another book from us so we held their feet to the fire the next time and said, “If you want to do it and you want another book, you’ve got to take this contract and delete that clause.” From now on, that’s done. There are still difficulties with publishers. For example, one of the more successful business books that we’ve written has been republished in several countries and in several languages and we are, at the very least, supposed to get copies of it in those languages. We got the Korean version, we got the Japanese version, but there were several others that we never got. They just didn’t get around to it. I believe there’s a Vietnamese version, but that’s a pirated version.

The other day, as a gift for my former collaborator, I gave her a copy of the Russian edition, which I had to go on Amazon and buy and have sent from Russia. I had to pay for this thing in Euros which I should have gotten for free.

Matty: It’s still exciting to see your work in all those languages. That’s very exciting.

Tony: Yes, it is.

Matty: I appreciate you going over both the art and the business, sometimes the underhanded business, of short story writing. I think that’s going to be really helpful to people. Thank you, Tony.

Tony: My pleasure. Thank you, Matty.